9 to 5. 5 to 9 to 5.

I’ve belonged to both.

Then I sought to get away from both.

It’s natural, I suppose.

Whenever I’m bound up, I want to escape.

When I’m free, I seek direction.

My four favorite films of June find people, symbols, institutions, and states see-sawing between forms of extreme order and disorder. Two Christopher Nolan films — Memento (2000) and The Dark Knight (2008) — narrativize the fundamental confusion between them. They either see chaos and order as two faces of the same coin. Or (if they see them separately from one another) express ambivalence over choosing either of them. The two other films — Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte (1961) and Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) — demonstrate why. Both films are set in post-Reconstruction-era Italy and Spain under Franco’s Dictatorship, respectively, representing opposite states of existence. Disorder and order both seem to alienate and stultify; each yearns for something they seem to have lost.

Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) is one of the exemplary documents of our desire to order the unordered and unorder the ordered. The film centers on Leonard Shelby, an insurance investigator with a short-term memory problem, attempting to track down his wife’s murderer. Its narrative structure is doubly ordered, overcompensating for our protagonist’s inability to remember his immediate past after 15 minutes. We move backward in time in color (we begin at the end and then track how we got there) to better understand how our protagonist (mis)understands things. Parallelly, we also move forward in time in black-and-white, piecing together the fragmentary strands of the color narrative. The trick is simple: combat forgetting by intricately plotting. (Nolan visualizes this repeatedly in both sections through permanent tattoos, photographs, and notes that Shelby uses to begin remembering).

But, the more the scattered puzzle pieces fit, the less our protagonist wants them to. Perfect order — built by accumulating the same documents, photographs, and tattoos he uses to remember — is too painful to process. So he devises a new trick to combat remembering: he willfully blurs, erases, and forgets.

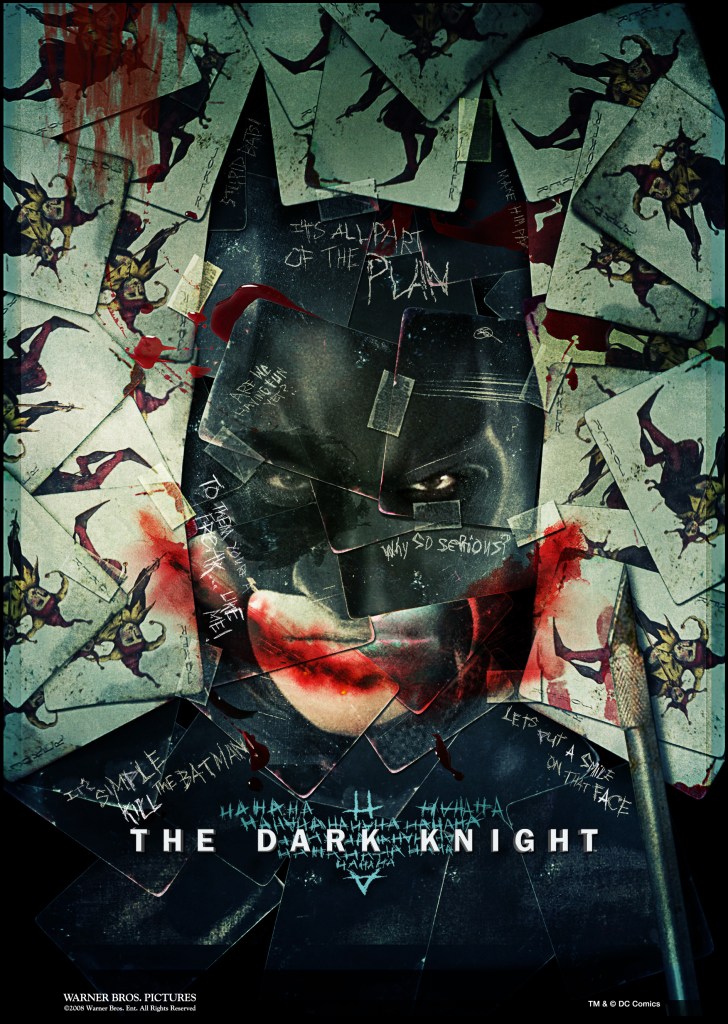

The immersive internal confusion of Memento is externalized in The Dark Knight — the centerpiece of his Batman trilogy. On the blockbuster’s jet black and steel grey industrial surface, the independent film’s unresolved dichotomies, perhaps, get overexposed. Order and chaos become key symbols here, represented by Batman (protagonist) and Joker (antagonist). We can easily distinguish good from bad.

But these symbols, supposed to be pure, are not. Nolan cross-cuts between Batman and Joker not only to contrast but also to confuse. Joker’s elaborate plans — from the thrilling opening bank heist to getting caught as a means of distraction — undermine his repeated claims of representing anarchy. Much more so than the state, he’s in control, orchestrating attack after attack that requires intricate planning. Batman, on the other hand, “improvises” to save the day. One of his final strategies to catch Joker is to hack all the electronic devices of Gotham’s people, something so out-of-order from what he believes to be lawful that it’s hard to not see as anything but rogue.

He does, eventually, manage to restore order. But it’s built on a lie.

The film’s climax involves the Leonard Shelby character of The Dark Knight — Harvey Dent, a.k.a. Two-Face. Nolan narrativizes his downfall throughout the film as a tragedy; he begins on Batman’s side but chooses to then become a version of the Joker. The Bat thinks the people must believe in Dent — the one whose face is white, unscarred, and unburnt. So he becomes the titular “Dark Knight,” preserving a false, easily corruptible brand of order that falls by the wayside like a pack of cards in The Dark Knight Rises (2012).

Why not choose total disorder, then? Why not live a life devoid of a governing structure that’s simultaneously hypocritical and suffocating?

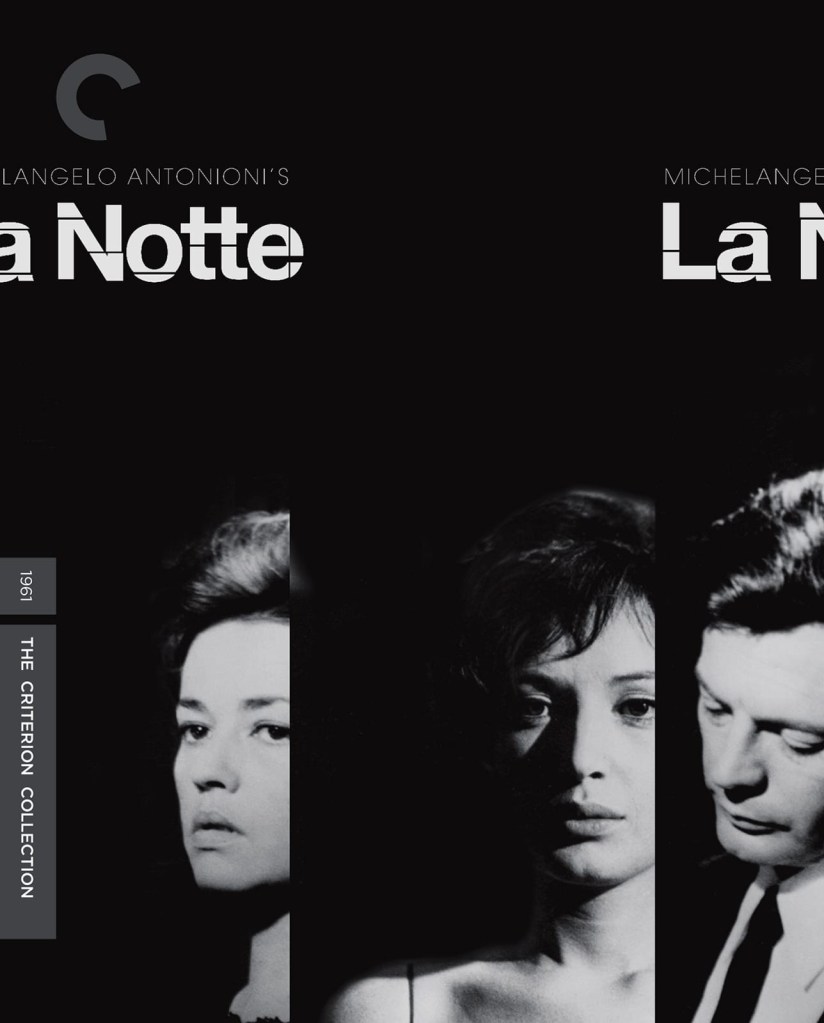

Antonioni’s La Notte, the second part of his Alienation Trilogy, is a film about a bourgeois couple — Lidia and Giovanni — who can afford this type of freedom. They’re free to do whoever or whatever, seemingly without any consequences. They’re not even duty-bound to each other.

For large sections of the film’s first half, we follow them separately. When we first see them visit their dying friend, Lidia leaves before Giovanni. As she waits outside, he’s seduced by a mentally ill woman, who he follows and kisses passionately. He pulls back only once the nurses get a hold of her. He seems to express a smidgen of guilt to his wife about this encounter, which she casually dismisses (“I understand. You were overwhelmed by it all”). Then, we see Lidia leave his book launch party early to roam Milan’s populated and abandoned streets. This section of the film abandons the talky-Bergman-esque drama that preceded it, playing out like a patient chronicle of an economically booming, spiritually barren Milan. Lidia encounters but continues to evade people and connections as Giovanni sleeps in his high-rise apartment, unperturbed by his wife’s absence.

Only in the film’s latter half (the titular “Night”) does the couple go together to an affluent party (Fellini’s La Dolce Vita-style). Again, though, they split as soon as they arrive at the party, pursuing romantic connections with different partners without necessarily feeling the need to respect their marital commitments (Giovanni, representative of Antonioni’s male characters, is particularly self-absorbed without being self-aware).

The diffuse plotting and lack of concrete action in Antonioni’s film represent directionlessness, not freedom. His characters — some knowingly, others not — have abandoned any sense of connection to organized thought and routine, becoming ghost-like creatures wandering through a city that reflects the same sense of un-belonging. (If anything imposes order on the characters, it’s the city’s gleaning, concrete, slick modernist architecture devoid of cultural identity). The characters yearn for their partner’s touch and eloquent words, not blank stares; they look back at a time when marriage meant something more than the nothingness they have now.

No one can quite comprehend anything other than their own bleak reality in Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive. Set in the early 1940s, right after the Nationalist army defeated the Loyalists, Erice portrays a fictional Spanish village in silent disarray. The adults, especially, appear similar to the characters in La Notte — all blank stares, quiet despair, and cryptic communication. Except, of course, in Beehive, they’re under total(itarian) order.

Erice uses children’s imagination — movie magic and fantasy — to combat the fascistic order’s catatonic reality. Centering his film around the wide-eyed six-year-old Ana’s search for the Monster after she watches Robert Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), the director consistently disrupts the somber tone with, at first, playful curiosity and, later, haunting moments of poetry. Ana’s Monster becomes many things — a remembrance of Loyalist soldiers who lost their lives but are forgotten, an actual surviving soldier looking for help, a ghostly figure more in touch with the War’s reality than the living themselves.

The effect of any of these interpretations is the same. Through their magical connection with Ana, they shatter the closed-off gates of reality; they jolt a collective consciousness on the verge of going into a coma.