Major spoilers for “Vertigo,” & “Om Shanti Om.” Minor ones for “Inception” and “Dunkirk.”

Cinema is engineered memories — a meticulous (re)construction of the intangible; an intercutting of precise technique and imprecise emotion; the (as late/great film scholar Gilberto Perez puts it) — “material ghost.”

My four favorite films of July highlight the very construction of filmic dreams to varying degrees. The first two — Alfred Hitchcock’s classic mystery, Vertigo (1958), and Farah Khan’s modern-day classic mystery-cum-Bollywood celebration/satire, Om Shanti Om (2007) — call attention most to their engineering. They’re neatly split into two halves, with the second functioning as a forced facsimile of the first, drawing attention to our (heterosexual, male) protagonists’ emotionally exploitative and destructive desire to duplicate the past in one scenario and his unexpectedly cathartic exorcism of past trauma in the other. The third film — Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010) — comes from a place of greater awareness: our (once again, male, heterosexual) protagonist knows he can’t reconstruct memories. So he tries to block them by engaging in an even more elaborate form of (heist movie) engineering, only to find it collapsing into his (guilty) subconscious memories. Relative to these three films, Dunkirk (2017) is least self-consciously interested in engineering. It’s still a Nolan film, so time-hopping experiments abound. But he conducts them all in the (historical) present; Nolan’s reconstruction of a moment in time as an experiential montage of survival and chaos feels most like pure memory because it emphasizes enthralling, emotionally charged confusion over a concentrated effort to linearly narrativize or explain it.

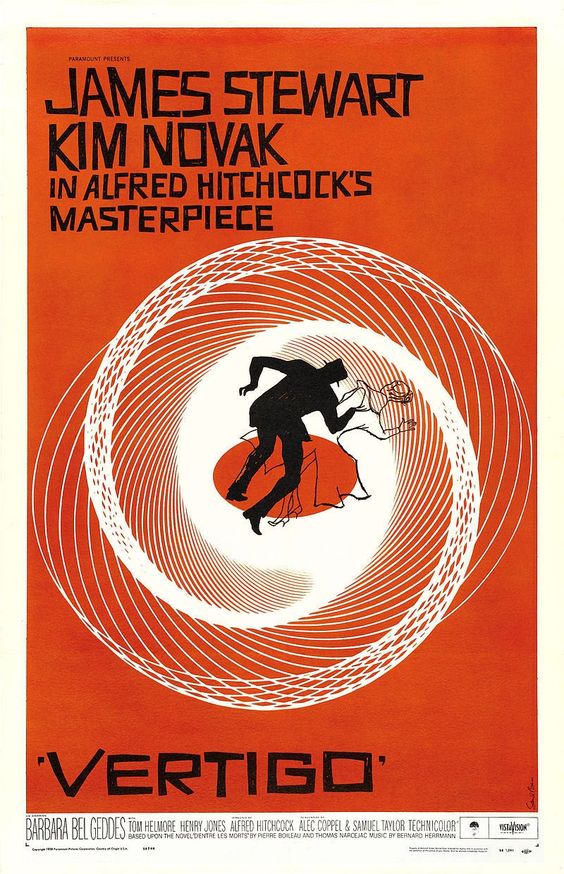

We begin, however, with Classical clarity. Narratively, that is. (The abstract “computer generated” Vertigo spirals, designed by Saul Bass and John Whitney for the film’s opening credits, deserve a separate discussion that’s not touched upon here). Our protagonist, detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart), retired from his all-action job after getting a fear of heights and vertigo during the film’s opening chase sequence, is asked by Gavin Elster, Scottie’s acquaintance from college, to follow his wife, Madeline (Kim Novak). Gavin believes Madeline is mentally ill, consumed by the myth of her supposed great-grandmother Carlotta Valdes’ murder (or suicide) at the hands of an unnamed, unfaithful, uncaring gentleman. Scottie, distant first, becomes increasingly enamored. After saving Gavin’s wife from drowning under the Golden Gate Bridge, the detective becomes romantically involved with her, trying, at every turn, to “solve” her psychosis to make her his Madeline.

It’s all — courtesy Bernard Hermann’s woozy soft-jazz score and Stewart and Novak’s simmering chemistry — incredibly dreamy and sexy if always slightly mysterious and melancholy. Until it’s just hauntingly sad, minus any romanticism.

Madeline’s “suicide” happens 87 minutes into the film’s 128-minute runtime; its twisty resolution follows twenty minutes later. The “accident” itself is a jolt for Scottie and us. But what sends us into a frenzy (before Scottie) is the film’s revelation that Madeline’s suicide was, in fact, a murder, elaborately planned by Gavin with his accomplice, Judy (also Novak). She acted as Madeline for a part of the insurance money but actually fell in love with Scottie.

Because our protagonist isn’t aware of this until the film’s perversely cathartic ending, the time spent after the audience becomes aware of this twist is Vertigo at its most pathetically painful. It’s when we see the detective-as-the-director forcing Judy — the short-light-brown-hair-colored, chatty, rebellious actress — to become Madeline — the blonde, quiet, submissive seductress. Scottie’s painstaking efforts at duplication are all cosmetic; he wishes to make Judy Madeline by dressing her up mannequin-like. There’s little to no regard for her actual sense of being. In doing so, Scottie becomes like Gavin, the unnamed gentleman, and Hitchcock (the director had a terrible reputation for his ill-treatment of actresses in his films). He, too, cures his vertigo problem by duplicating the “murder” of Judy/Madeline/Carlotta Valdes accidentally.

While Om Shanti Om prompts a similar interrogation of its male protagonist(s), it does so only briefly. Its “happy” accidents and character realizations side-step self-critique to highlight the healing power of filmic engineering while proving its inability to duplicate what’s lost to time.

Khan’s film, even more so than Vertigo, is evenly split into a before and after. The before is the late 70s and early 80s Bollywood. It’s a simple, if still sharply divided time, expressed through the star-crossed romance between an aspiring actor-cum-junior artist, Om Makhija (Shah Rukh Khan), and the “Dream(y) Girl” herself, Shantipriya (Deepika Padukone). She notices him because he saves her from a fire that breaks out on set; he thinks that means she’s in love with her. But, as was commonplace in the industry then, the star actress is secretly married to mega-film-producer Mukesh Mehra (Arjun Rampal). When she threatens to reveal this and her pregnancy to the press, Mukesh hatches a plan to kill her to preserve his reputation. Om, already heartbroken, finds this out and tries to save Shanti. But Bolly-fate disapproves of this; both Om and Shanti die.

The after, however, sees the story repeat itself in 2007. Except Om Makhija is now Om Kapoor (short for OK; also played by SRK) — the industry’s shining (also nepotistic, overacting, brat) star. He seems to have some connection to the past: his fear of fires and sudden audio-visual bursts of Shanti painfully screaming link him back to Om. But he’s ignorant of these signifiers until he sees Mukesh (now a Hollywood producer, going by the alias of “Mike”). Upon shaking his hand, he realizes the legitimacy of his connection to the events that took place in the first half, prompting him to (re)stage the production of “Om Shanti Om” — the film that Mukesh was supposed to make with and for Shanti, but, instead became her murder site. OK’s intention is to re-create, re-illuminate, and re-member personal trauma cinematically to make Mukesh fess up his crimes.

For this, he needs a Shanti-look-alike. This is where OSO becomes a narrative look-alike of Vertigo (other endless layers of duplications of Bollywood classics that may themselves be photocopied Vertigos are not addressed here). After a hilariously parodic montage of actor auditions, OK finds Sandy (also played by Padukone) — a ditzy super-fan of OK whose facial appearance matches Shanti’s. The subsequent montage — OK and his crew trying to dress Sandy up like Shanti and telling her to perform like she did — is straight out of Vertigo’s “dress-up” phase.

But in OSO, this happens 45 minutes before the film’s climax. Even more importantly, the broadly comedic tonality of the scene and its immediate, gravely serious resolution push the film away from becoming a dramatic tragedy. After berating Sandy for her inability to channel Shanti’s persona, Om apologizes, explaining why it is essential for him that she obliges to his di(re)ctatorial demands. This sequence (and Sandy’s somewhat perversely ornamental role itself) highlights how OK, unlike Scottie in Vertigo, knows the fundamental difference between engineering and memory; he knows that Sandy’s performance of Shanti will not equal Shanti.

It’s a grand, constructed (re)creation that the film acknowledges as just that most when Shanti’s literal ghost takes center stage during its climax. It’s OSO’s moment of genuine catharsis; Khan finds the unlikely intersection between filmic materiality and ghostly presence, where the latter somehow works together with the former to provide us what the film has repeatedly told us we crave — a happy ending.

Inception features no such synchronicity. By and large, it’s a narrative freight train, a near-constant barrage of exposition and action. Its thrilling opener is about “extraction,” — the cut-throat process of stealing secrets by infiltrating people’s minds (Nolan makes us experience this by throwing us directly into a dream and then pulling out). Then, its extensive set-up is about “inception” — the much more challenging process of implanting ideas into people’s minds. Here, we’re thrown into the deep end of impersonal but fascinating mechanics and logistics — how do we con the person’s “subconscious security” into believing our elaborately orchestrated deception? How do we design each dream level differently to ensure we have enough time in each of them? How loud does our “kick” need to be on one level so that we can hear it in the next? How and when do we synchronize it, etc etc. Nolan’s characters talk and talk and talk and talk before showing us the execution of their magnificently intricate three-to-four dream-level plan, which the director’s meticulous chris-crossing exemplifies even more.

And yet what stands out most is the faultiness, the hurdles — not ones imposed by their target’s “subconscious security” system but the ones created by our director-in-command-of-the-heist’s subconsciousness. Throughout the now-much-derided expositional first half, Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), our protagonist, tries to keep himself away from planning the dreams, from knowing the heist’s particulars. He fears that despite his highly skilled subconscious infiltration training, he can’t contain the consistently erratic bursts of his past, primarily manifested in the form of his now-dead-wife, Mal (a seductively thrilling Marion Cotillard), threatening to sabotage his present and future. The problem is that these spontaneous impressionist images are (cross)cut with the same Swiss knives used to tailor the dream heist. It’s just that Cobb isn’t the one operating them.

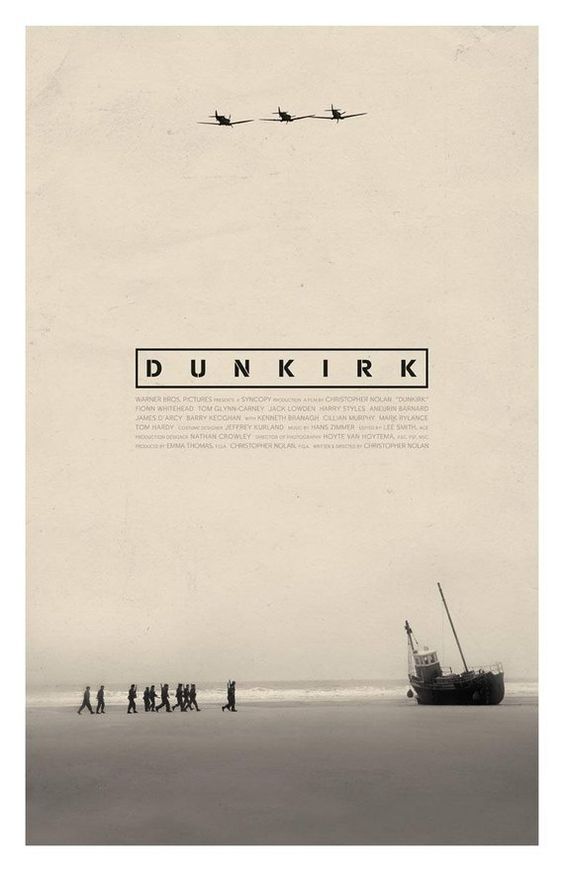

Dunkirk is this spontaneous flow of steel blue, grey, and beige imagery expanded to a feature-length film. I exaggerate, of course. But two critical differences between Dunkirk and all the other films discussed here push it closest to feeling like an act of engineered memory that doesn’t call attention to its status as that. First, there is no before and after in Dunkirk. The film chronicles a particular moment in time: the miraculous evacuation of allied soldiers belonging to British, French, and Belgian forces as the German Army began invading the beaches and harbors of Northern France. Second, it features no definite protagonist. No one other than Nolan controls the narrative; the soldiers’ and rescuers’ lives outside of escaping, of survival are omitted. What remains is the filmmaker’s engineering — his penchant for a chris-crossing triptych structure vs. a linear one — that, understandably, distracts the film’s detractors.

But its effect on me is the precise opposite. The cross-cutting destabilizes the film’s temporality, imbuing it with a near-consistent feeling of chaos despite being rigorously planned. It’s perfect, really — history (re)created in fragments, intended to be whole but always replete with holes.