This academic paper is a close analysis of Marguerite Duras’ “India Song” (1975). Spoilers for a movie that can’t really be spoiled.

INTRODUCTION

We open with an establishing shot of a hilly landscape during what appears to be a sunset. The reddish-orange sun and the dark green valleys occupy the top and bottom halves of the frame, with the film’s white-colored credits taking their place in the middle. The orientation of the colors seems important because it matches that of the Indian national flag, suggesting we must be there.

During the entirety of its four-minute and fifteen-second runtime, though, this shot offers little to no concrete evidence that this is, in fact, India. If anything, both the visual and audio signifiers, suggest otherwise. For one, the longer we watch the sunset, the further the film disassociates itself from mimicking India’s flag colors. The saffron dissolves into navy blue; the whites of the title credits disappear after informing us who made the film. What is left is a post-card image of a landscape devoid of any cultural marker – monument, ornament, person, instrument, or document – that signifies specificity.

Then, there is the audio. In sharp contrast to the lack of information the opening image provides, the layered sound mix provides an excessive amount. Critically, though, without any context. There are a total of four different audio tracks that vie for supremacy in this extended establishing shot. One of them sounds like the most natural fit, i.e., the diegetic sound for the shot. However, it occupies the least time on the soundtrack. The two most prominent voices in this shot come from two women speaking different languages. The first one switches between singing a melodious lullaby and adamantly ordering someone. The second, French one, subtitled for the viewer, attempts to identify the first voice as that of a Laotian “Beggar Woman.” It feels like the interplay between these voices will fill in the gaps left open by the image. However, hardly any mention of India arrives, with the melancholic piano score punctuating the shot, only displacing us further from India because of its European orchestration.

This absence of India remains present throughout Marguerite Duras’ India Song. Deliberately so. The film’s production took place, not in India but in Paris. The Château Rothschild stood in for the central location in the film – the French Embassy in Chandernagore, Calcutta, in the 1930s. Moreover, Duras chose not to look at period-specific photographs of India but instead re-create the place through her memories.

Her approach to making a film about a foreign, previously French-colonized country is unorthodox, suspiciously detached. But that is also what makes it so formally innovative and daring. Duras’ India Song limits itself to capturing the lives of the French colonizers in India, namely that of Anne-Marie Stretter, a bored wife of the French ambassador. By doing so, the filmmaker restricts her protagonist and her own gaze to stay within the walls of French colonized India.

This paper will focus on how Duras visualizes this feeling of stuck-ness. Using long static takes primarily situated within the French Embassy, Duras aims to isolate her characters within their decadent, dilapidating Embassy. Even when there is a chance to move away from it (via the camera’s mobility or the audio tracks’ synchronization with the visual track), the French filmmaker pulls them right back. Her characters can hear their thoughts, traumas, gossip, and news of worldwide events. However, they cannot see or even begin comprehending what is outside their mansion.

MOTIONLESS

The easiest, most effective way to emphasize the colonizers’ stasis is to keep the camera in a fixed position for the longest possible time. This lack of camera movement and minimal cutting hampers forward momentum – physically, narratively, and emotionally. For the slightest pan or tracking movement signals an intention on the filmmaker’s part to move on from a particular place and time to a different one. Similarly, a cut allows for a quick shift in focus.

Duras largely denies her characters both movements and (short)cuts. India Song boasts a remarkably high average shot length (ASL) and high static shots to movement shots ratio (ST/MT), exemplifying the extent to which the director keeps her characters rooted in the colonial mansion.

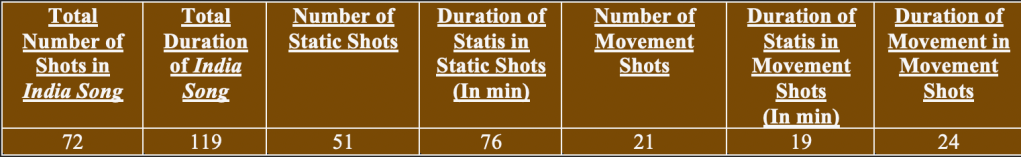

The ASL is a valuable metric to determine this film’s consistently languid pacing. We calculate it by dividing the film’s total runtime (here, 119 minutes) by the total number of shots in the film (here, 72). For India Song, this gives us an average shot length of 1.65 minutes (approximately 99 seconds).

Not only is this ASL exponentially higher than the traditional mean for Hollywood films (~ 4-6 seconds), but it is also higher than European art-house filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky (~ 40 seconds), known for making “slow” films.[1] The comparison is valuable as it helps situate Duras’ long takes as boundary-pushing relative to art-cinema.

The long takes here feel even more grueling because of how much they are devoid of any movement. The ST/MT ratio measures the number of shots the camera is static divided by the number of shots it moves. For India Song, the ST/MT equals 2.43, indicating that Duras uses static shots nearly two-and-half times more than she uses camera mobility. Still, this number is an underestimate. The lack of camera movement here does not consider how much the camera is in stasis during the shots that feature movement.

For this, it is helpful to determine the film’s total duration of camera immobility. That is, the duration that the camera is static in the static shots plus the duration the camera is static in the movement shots. The fifty-one static shots comprise approximately 76 minutes of the film. Of the remaining 43 minutes comprising movement shots, only 24 actually feature a mobile camera. The remaining 19 minutes are, again, static. Therefore, the camera is immobile for approximately 95 minutes of the film’s 119-minute runtime, demonstrating the extent to which Duras keeps her characters from seeing anything remotely other than the French Embassy.

DIRECTIONLESS MOVEMENTS

The spareness in camera movement gives its mobility added importance. We expect the few tracking shots, the pans, and the tilts to signify something about the film’s narrative thrust; clarify its characters’ goals, especially when this movement happens consecutively.

Only four sequences in India Song feature two (or more) consecutive shots with movement. Any form of movement – pan, tilt, track, crane – counts.

Here too, though, stasis looms large. The hard cut from one shot to the next happens after the camera stands still. In other words, for all these sequences, the camera tends to stop, move, then stop again (see the Pattern of Movement/Stasis), suggesting a return to immobility within the shot’s duration.

Except – the first, here titled, “The French Embassy.” Unlike the film’s static first shot, this sequence introduces its central location and protagonist through two consecutive movement shots implying spatial specificity and mobility. Before this, the film only provided fragmented information about its time, place, and people. The non-diegetic, asynchronous voices of the Laotian “Beggar Woman” and the French gossipers cohered and contradicted the static images, with the melodic India Song only adding to this confusion. However, here, especially from the very end of the sixth shot to the first twenty-five seconds of the seventh (that lasts ninety-two seconds), Duras promises us a way forward.

The synchronicity of image and sound is critical here. Unlike large sections of the movie, Shot No. 7’s first twenty-five seconds seem to take place in real-time, with the images complementing the French woman’s statements about the location. Shot No. 7 begins by answering the question – “Where are we?” – at the end of Shot No. 6. For the first time in the film, we see a (low angle) exterior shot of this dilapidated building. As the camera tilts down, almost scanning for clues to describe the place to us, the voice-over answers, “The French Embassy, India.” Then, as the camera changes its motion, gently tracking from left to right while simultaneously panning left to right, the narrator begins to add more details to the image. Again, the more the camera tries to see, the more the voice-overs fill in details that it observes.

However, Duras disrupts this briefly established continuity in two critical ways as the shot progresses. The first, more noticeable change is in the sudden disjunct she creates between what we hear and see. As the camera continues to track left to right, we expect the voice-over to continue informing us about the French Embassy or India. But the French woman abandons giving details about the place. Instead, asking, “When she died, he left India?” This change in topic is disorienting on two counts. First, we do not know who “he” or “she” really is because the film has not formally introduced us to them at this point. Second, the French woman’s immediate shift from talking about the location in the present tense to the events that took place (here?) in the past tense makes us wonder if the tracking shot represents some sort of time-lapse. It destroys the spatial and temporal continuity previously associated with the tracking shot.

The second subtler shift occurs visually. Here, again, Duras emphasizes her, her camera, and her characters’ restricted gaze. As the French woman begins interrogating the woman’s death on “The Islands,” the camera stops tracking, tilting up gradually to then pan left to right for the last thirty seconds of the shot. The revelations to this mystery that took place on the islands invite speculation from us, wanting us to either see this place via a cut or be able to move towards it via the tracking shot. Instead, Duras fixes the camera at that moment, restricting direct or even closer access to it.

While breaking down each shift in camera movement and its complicated relationship with sound reveals Duras’ consistent disruption of continuity and coherence, the continuous tracking or panning from left to right overrides those micro-disruptions. The panning motion that ends the shot, in particular, mimics the clockwise movement, suggesting that whatever we see in the next shot will follow whatever has just been shown or said.

However, the hard cut to Shot No. 8 destroys any possible expectations set by the overall camera movement in the previous shot. Duras does not just deviate slightly from what she established in the previous shot; she actively opposes it. Here, the camera is situated in the interior of this decaying mansion, slowly panning right to left to introduce the protagonist of the film (whom the film has just told is maybe dead!) dancing with her partner (the “he” in Shot No. 7) to India Song.

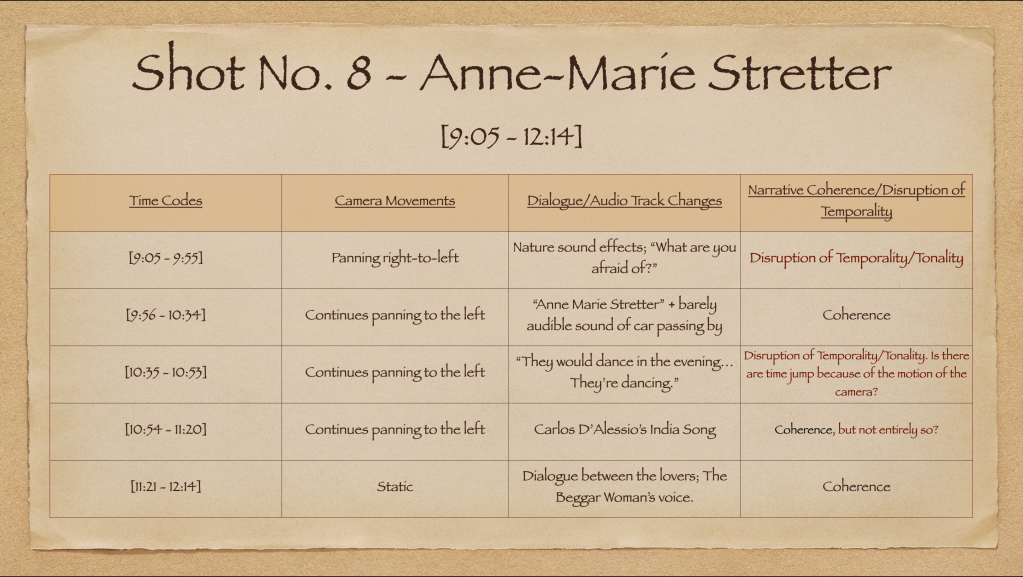

The machinations of this shot are like those in Shot No.7 in that they hint at continuity and coherence but provide enough temporal dissonances never to provide much narrative momentum. The reveal of our main protagonist’s name has (somewhat of a) audio-visual synchronicity. As the camera pans from right to left, two non-diegetic audio tracks occupy the image of a brightly lit, seemingly abandoned drawing room with open windows overlooking the forest. The first one is birds chirping, highlighting the open spaces within the mise-en-scene and the natural greens in the background. The second, more overpowering, is the French woman’s grave, scared voice that, at the start of this shot, cryptically asks, “Who are you afraid of?” The closer the camera pans toward Anne-Marie Stretter’s photograph, the louder, more pronounced this audio track gets. The sounds of nature drop out, leaving the image of an incense-smoke-covered photo of Stretter complementing the French woman’s whispered, slightly haunted enunciation of the film’s protagonist.

However, the next forty seconds of this panning motion disrupt this established continuity. Akin to the abrupt change in tonality in the previous shot, the French woman changes the subject and tense right after establishing our central character. Rather than fearing the protagonist, the French woman, now romantically, recalls a specific detail about Stretter and her lover. Furthermore, she now refers to them in the past tense, dislocating the temporal continuity established before.

This push-and-pull between brief coherence and elongated contradiction between the image and sound is present throughout India Song to show the endless ways Duras restricts her characters’ movements. What “The French Embassy” sequence expresses most forcefully is the pointlessness of even attempting to move forward as the camera will pull you back regardless. Such is the contradiction between the clockwise pan in Shot No. 7 and the counterclockwise one in Shot No. 8 that there seems to be no movement. Essentially, the two shots seem to cancel each other out.

It is important to note that these shot movements are not even close to perfectly symmetrical. The seventh shot involves the camera tilting, tracking, and panning from left to right. On the other hand, the eighth is an elongated pan from right to left. So, even though it may feel like the characters are fixed to the same place the camera is before this sequence takes place because the overall direction of the shots cancels out, it really is more ambiguous than that.

Perhaps, this form of movement has displaced Duras’ characters further, making India even more elusive.

Bibliography

- Schrader, Paul. “Rethinking Transcendental Style.” In Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, 1st ed., 1–34. University of California Press, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv6p4jq.4.

[1]. Vashi Nedomansky, “Average Shot Lengths of 7 European Directors (Ingmar Bergman & More),” Vashi Nedomansky (Blog), January 8, 2019, https://vashivisuals.com/average-shot-lengths-of-7-european-directors/.